Cedar trees, known in Japan as Sugi (Cryptomeria japonica), are evergreen coniferous trees that spread across the nation, playing an integral role in daily life. They thrive in groves, making up almost forty percent of the forest canopy. Several prefectures, such as Kyoto, Nara, and Mie, designate them as emblems of their regions.

Walking along the path of an ancient temple, like the one in Okuin, Koya-san, you feel transported to another world, surrounded by thousands of Sugis towering above you. The air seems to shift around their reddish-brown trunks, and it feels appropriate to offer a greeting or a prayer to these dignified beings.

Historically, these trees were the backbone of the country. During the Edo period, the straight grain of cedar wood made it indispensable for constructing pillars and beams. Despite the turmoil of the Meiji era, when Japan fought wars with Russia and China, and later in the Showa era against the United States, Sugi remained a core building material. After World War II, however, Japan entered a phase of reconstruction, followed by an influx of cheap imports that diminished demand for domestic lumber. Today, vast acres of mature cedar stand unclaimed, while the forestry workforce continues to decline.

Sugi timber has a resinous, almost intoxicating fragrance, and the wood is flexible and naturally resistant to insects. While construction remains a primary use, the appeal of these trees goes beyond their practicality. Cedars grow with a smooth, vertical precision that is rare among hardwoods like camphor, which often have curled limbs. Their bark peels in fine red-brown ribbons, and each spring, they release yellow-tinted clouds of pollen that trigger bouts of sneezing in towns and cities.

In Kifune, Kyoto, the Aioi Sugi, believed to be around a thousand years old, splits into two colossal trunks while remaining anchored by a single root system. Further south, in Kumamoto, Kyushu, the thirteen-century-old Amida Sugi narrowly escaped being sold in 1902, as townspeople pooled their resources to reclaim it. Today, it spreads out impressively, watching over the community.

On Yakushima Island, Sugi takes on a mystical form. The Jomon Sugi, thought to be over three thousand years old, beckons travelers on a seven-hour trek through drifting fog and moss-shrouded stones. Collectively known as Yakusugi, these cedars over a millennium old inspired Hayao Miyazaki’s vision of the rich green realm in his film, Princess Mononoke. After Yakushima earned World Heritage status, tourists flocked to the area, which led to the erosion of trails and exposure of tree roots. Locals responded by reinforcing the pathways and reminding visitors that protecting these ancient trees requires caution and respect.

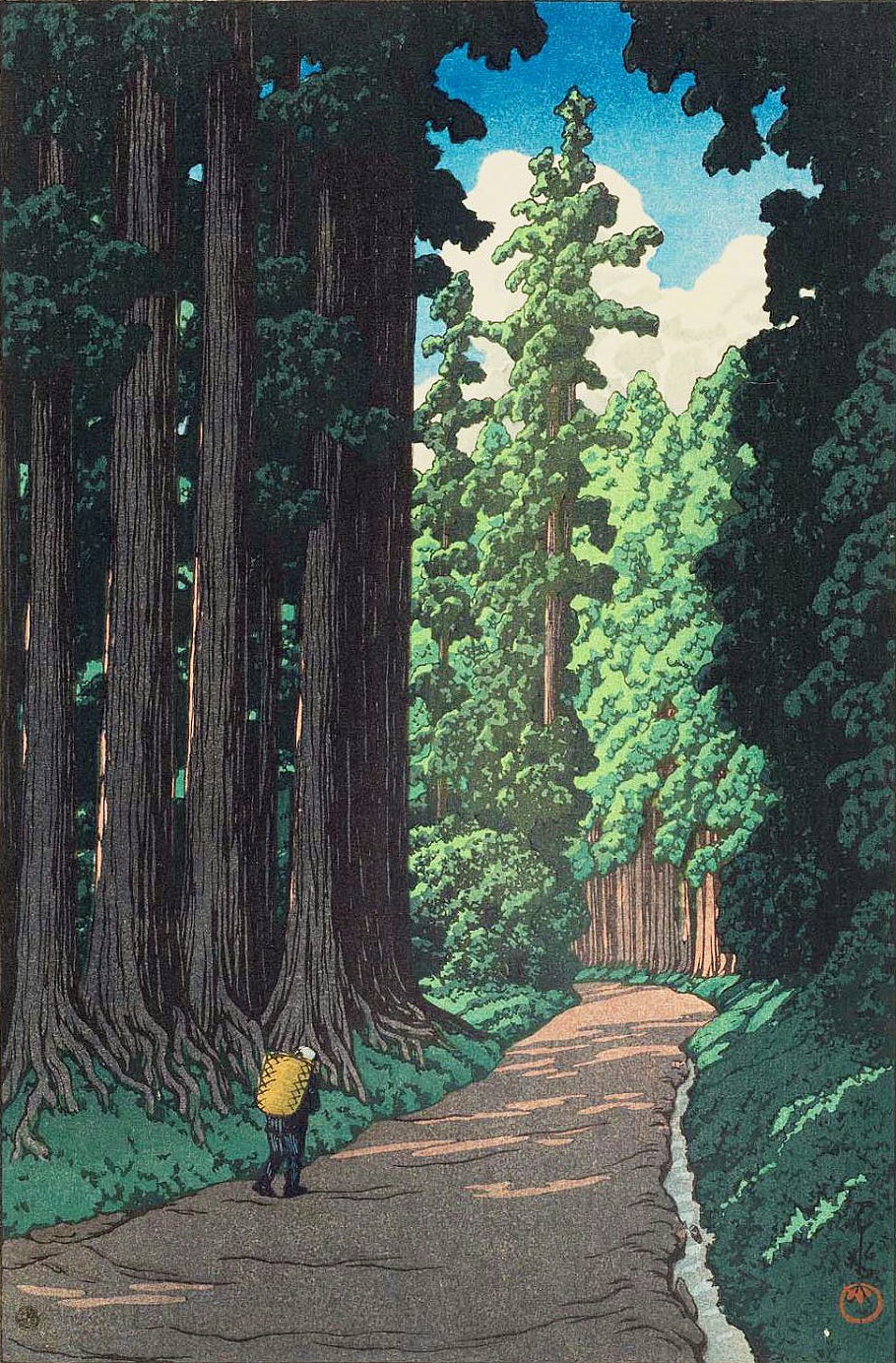

In Nikko, north of Tokyo, a thirty-seven-kilometer avenue of cedars holds the Guinness World Record for the longest tree-lined road on Earth. This avenue was planted over two decades by feudal lord Matsudaira Masatsuna, who served three generations of Tokugawa Shoguns, as a donation to the Toshogu Shrine. The trees’ crowns, forming a stately corridor, were chosen for their sky-reaching form, believed to harbor a divinity worthy of guiding pilgrims to sacred ground.

Beyond Japan’s shores, Cryptomeria has been introduced to the Azores in the mid-19th century for logging and to north-eastern India for constructing homes. Back home in Japan, countless cultivars of Sugi exist, from miniature bonsai to ornamental garden varieties and vast commercial tracts, showcasing the adaptability of this species. Interestingly, the name we use—Japanese cedar—is a misnomer, as Sugi is not a true cedar but belongs to the cypress family Cupressaceae. For centuries, Sugi has been an important tree species in Japan, appearing in Manyoshu, the oldest surviving collection of waka poetry in the country. Although their pollen can be problematic during certain times of the year, they are a familiar presence, much like a family member who can be difficult at times but is ultimately loved.

References

EN

JP

I really enjoyed reading this, such beautiful trees and gorgeous photos. Also the print if Road to Nikko is one of my favourites. Thank you.

The smell of a sawmill that has been cutting sugi into planks is wonderful. Based on the number of sugi on the hillsides and the regular cutting of them I think plenty people use them for something. I assume buildings but maybe something else.