The sea off Fukui’s Tojinbo cliffs is cerulean, its crests colliding in white seams that crash with endless energy. Hawks wheel overhead, hoping someone will drop a cone of vanilla soft-serve. Wind drums the basalt pillars, and for a moment the whole ledge feels as if it might lift beneath your feet. Then the black pines come into focus, their thick, twisted trunks zigzagging after years of battering gales. You catch your breath; the cliff suddenly feels less perilous.

Black pines (Pinus thunbergii) take to harsh coasts with aplomb. They shrug off brine, flex under snow, and trade nutrients with mycorrhizal allies hidden in lean sand. Long before concrete seawalls, fishing villages planted rows of these trees to tame drifting sand and typhoon winds. Monocultures, though, invite trouble in the form of pests and diseases so forestry agencies now weave other species into the groves to build stronger coastal forests. But the black pine keeps pride of place.

Nowhere is this clearer than in Rikuzentakata, Iwate Prefecture. In the wake of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, a lone pine remained where seventy thousand others were swept away. Locals called it the “Miracle Pine” and it became a symbol for the city. The lone tree eventually succumbed to damage from seawater, but the locals preserved it by hollowing out its trunk and inserting a steel shaft and concrete base to create a monument.

Ingenious defenses appear elsewhere too. For centuries Niigata’s coast battled sandstorms that buried homes and fields. In the Edo period, a townsman named Gocho Kinshichi developed the sudate method, where bamboo and reed screens formed artificial dunes to trap the sand. Black pines were planted behind these screens, turning disaster control into landscape art.

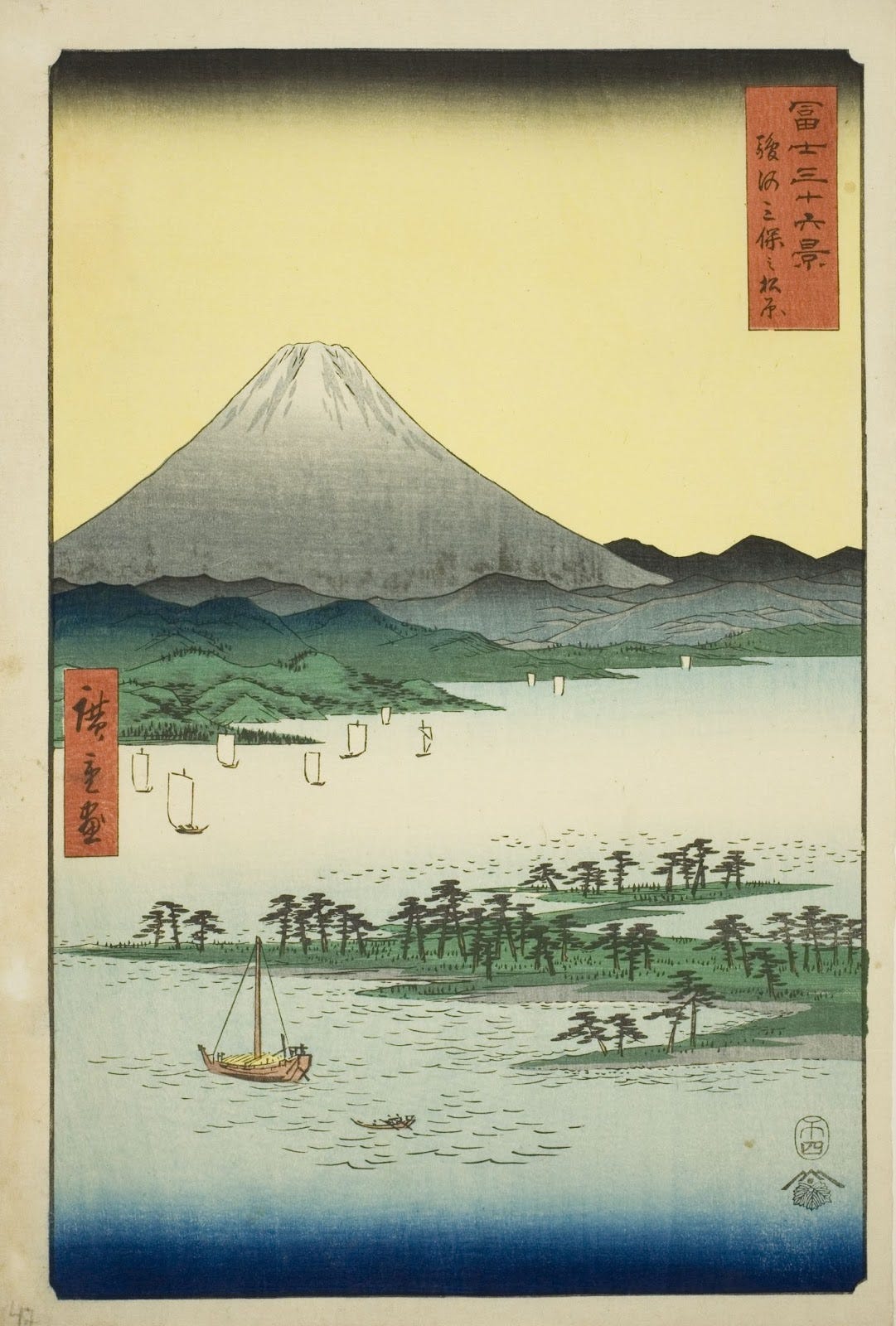

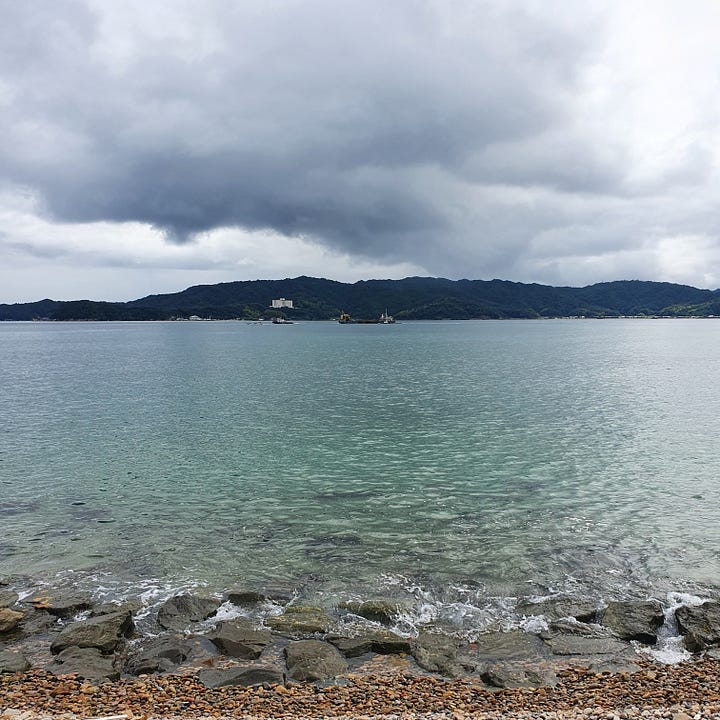

Many of these shores are now celebrated for their beauty, inspiring generations of artists and poets. Amanohashidate in Kyoto Prefecture, known as one of Japan’s three most scenic spots, is famous for its 3.3 km-long sandbar covered with thousands of black pines. The name “Amanohashidate” means “Bridge to Heaven,” and it’s popular for visitors to bend and peer between their legs to view the scene upside-down, seeing the pine-clad sandbar stretching across the water as if it were a path floating toward the heavens.

Perhaps walking through the pine grove itself offers a more magical experience. The white sand, glimpses of the shimmering blue sea through the pine branches, and the peaceful atmosphere make it a place where the sea feels gentle, and the forces of nature seem less raw than those at Tojinbo in Fukui.

There’s something deeply comforting about encountering these black pines repeatedly on journeys along Japan’s coasts. They seem to wrap you in an embrace, offering a sense of protection, and you can’t help but feel warm and hopeful, knowing you’ll encounter these kindred spirits once more. When you do, perhaps they might teach you a thing or two about the art of survival.

References

EN

https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/society/general-news/20230311-96669/

https://www.rinya.maff.go.jp/j/kaigai/pdf/keynote_final_english.pdf#:~:text=Yet%2C%20although%20coastal%20forests%20have,are%203%20meters%20and%20below

JP

http://www.town.mihama.wakayama.jp/docs/2014011800076/

https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/shinngikai_blog/hukkyuukeikan/tebiki/tebiki.pdf

https://dl.ndl.go.jp/view/prepareDownload?itemId=info%3Andljp%2Fpid%2F11065944&contentNo=1

https://www.maff.go.jp/j/pr/annual/pdf/kaigan_bousairin.pdf

https://www.pref.niigata.lg.jp/sec/niigata_norin/1220983405876.html

Sadly, black pines are susceptible to the pine borer beetle and that seems to be spreading gradually all over Japan. I wrote recently about the ones on the Goishi Kaigan, next door to Rikuzen Takata, which are visibly suffering and dying from the beetle - https://lessknownjapan.substack.com/p/goishi-kaigan?r=7yrqz

Here in Shimane the (expletive) beetles have radically changed the coastal landscape from what I recall when I first came here some 30 years ago and they have killed a number of really old pines in the process including one in Gotsu that was several hundred years old