When you crave an easy-to-eat snack that still feels satisfying, dango are excellent contenders. These bite-sized dumplings—traditionally served on skewers—offer a soft, chewy texture that pairs beautifully with sweet or savory sauces. One of the most popular preparations features a sweet soy sauce glaze. Dango remains integral to Japanese culture, enjoyed throughout the year at festivals and important events.

Origins and Early History

Legend has it that dango date as far back as the Jomon period. In those ancient days, people would grind acorns, remove the bitterness by soaking them in water, and then shape the powder into dumplings. Over time, rice flour became the primary ingredient. At Kyoto’s Shimogamo Shrine, for instance, families in the surrounding area would prepare rice flour dumplings to offer to the gods. Even now, the famed shop near the shrine, Kamo Mitarashi Chaya, grills five dumplings on a bamboo skewer and tops them with a sweet-and-sour soy glaze.

Regional Specialties

From north to south, every region of Japan has its own take on dango. In Takayama (Gifu Prefecture), the dumplings are grilled, dipped in soy sauce, then grilled again for a rustic, smoky finish. In the village of Anamura in Kusatsu (Shiga Prefecture), a confectionery shop named Yoshida Tamaeido is known for selling fifty fan-shaped dango—local folklore holds that a famed clinic nearby once attracted legions of visitors. Meanwhile, Iwate Prefecture has a New Year’s Eve tradition of making colorful dumplings and hanging them on branches of mizuki (willow) trees to pray for a bountiful harvest; these festive creations are called “mizuki dango.”

Seasonal motifs

Dango change with each season too. Hanami Dango, in pink, white, and green, accompany spring cherry blossom viewing. They are colorful, and pleasant, a sure sign of spring. Kusa Dango, infused with yomogi herb or mugwort, captures late spring’s fresh flavors. Higan Dango, offered during the equinoxes, honor ancestors in both spring and autumn. Tsukimi Dango, stacked to resemble the harvest moon, symbolize gratitude for nature’s bounty in autumn. The wagashi or traditional sweets sections of supermarkets is always a good place to check the current seasonal dango.

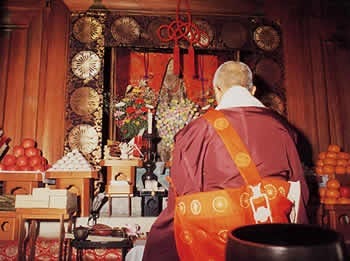

Spiritual Significance

Though Japan does not have an official state religion, many people observe Shinto and Buddhist customs. During the spring equinox, for instance, families in various regions offer “higan dango”—round, white dumplings—to honor their ancestors. According to Buddhist belief, the worlds of the living and the dead draw closest at this time. Over in Miidera Temple (Shiga Prefecture), a mid-May festival is held for the goddess Kishimojin. Originally a scary spirit who preyed upon children, Kishimojin changed her outlook when Shakyamuni Buddha intervened—hiding her own child to show her the pain she inflicted. She embraced Buddhism, and transformed into a guardian of children, and a goddess of fertility. In her honor, a thousand colorful dumplings made to look like flowers are presented to commemorate the souls of the children.

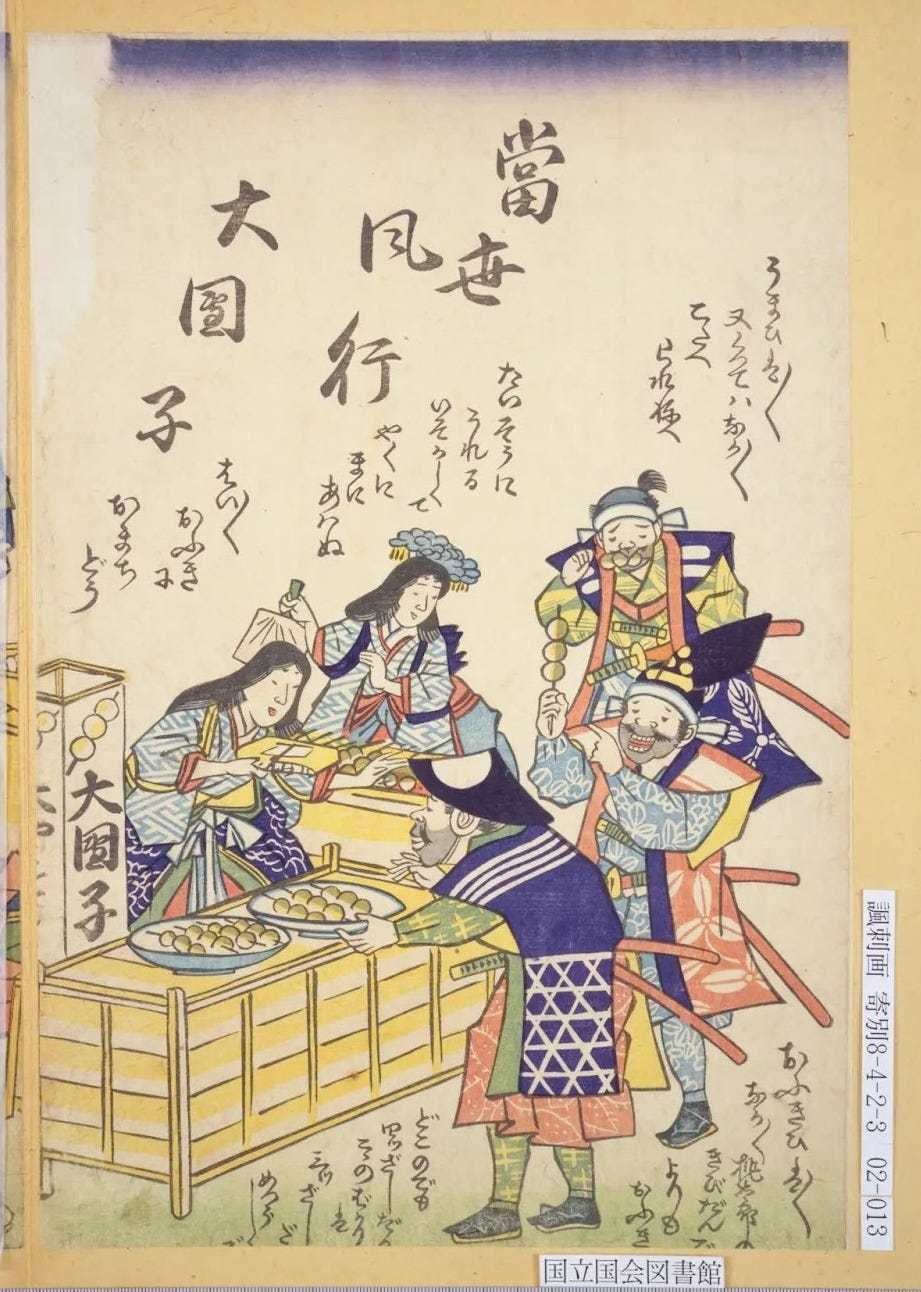

Dango in the Edo Period

By the mid-Edo period (1603–1868), dango had firmly captured the public’s imagination. One famous figure associated with these dumplings was Kasamori Osen (1751–1827)—reputed to be one of the “three beauties of Edo” and daughter of a tea shop owner near Yanaka Kasamori Inari Shrine. Visitors flocked to see both the shrine and Osen herself, who appeared in popular ukiyo-e prints by Suzuki Harunobu and inspired Kabuki plays and poetry. In one poem Osen and the main character recite poetry about the wonders and variety of dango from mugwort dango to tanuki dango.

Modern Popularity

Fast forward to 1999, and one event in particular helped establish dango as a firm household dish: the release of the NHK song “Dango San Kyoudai” (団子さん兄弟). Depicting three playful, close-knit dango siblings, the tune became an instant hit among children and adults alike, sparking a nationwide dango boom. Traditionally, the number of dumplings per skewer varies by region—four is standard in the Kanto area, while five is more common in Kansai. However, with the song’s emphasis on three siblings, some shops that had sold four or five dango on a skewer began switching to three, proving that even a centuries-old treat can adapt to modern trends.

One version of the song dango san kyoudai. The original song

There’s a timeless simplicity to dango that transcends passing trends. Their remarkable versatility—ranging from classic white dumplings to colorful, ingredient-driven varieties—suits both traditional and contemporary settings. While many shops now experiment with strawberry- or chocolate-flavored versions, there’s nothing quite like the subtle, herbaceous aroma of mugwort dango grilled over charcoal, or the sweet, savory bite of mitarashi dango dipped in a rich soy glaze.

Note

Where to try dango: this is just a small sample in Kyoto, Tokyo

Tokyo

Kibi Dango Azuma (きびだんごあづま):

https://www.google.com/maps/search/?api=1&query=きびだんご+あづま

Kyoto

Kamo Mitarashi Chaya (加茂みたらし茶屋):

https://www.google.com/maps/search/?api=1&query=加茂みたらし茶屋

References

Kamei, Chihoko (亀井千歩子). 47都道府県和菓子 Tankobon Hardcover

和菓子を愛した人たち Tankobon Softcover 虎屋文庫 (著 (その他)

Akai, Tatsurō (赤井達郎). 菓子の文化誌

https://www.maff.go.jp/j/keikaku/syokubunka/k_ryouri/search_menu/menu/34_29_tokyo.html