Japan's Cities Gripped by a Wave of Bear Attacks

It’s hard to open the news in Japan these days without seeing something about bears. Forget mountains, in some cities they’ve appeared in supermarket aisles and even at hot spring resorts. I am Sneha Nagesh and in this edition of Secrets from Japan & Beyond, I look at why bear sightings are increasing, what’s driving bears closer to human settlements, and introduce some of the most memorable bear stories, from the infamous brown bear OSO18 in Hokkaido to the hunters and villagers still living alongside them.

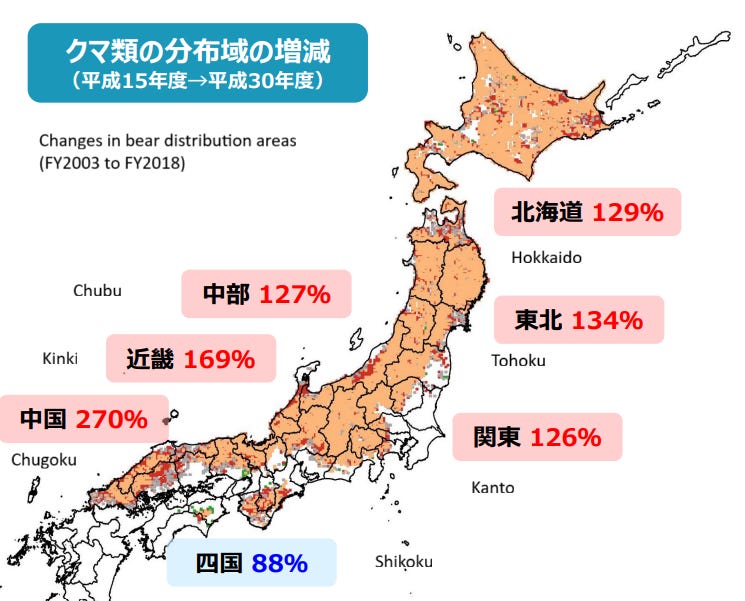

There has been a steady increase in bear sightings and attacks across Japan. In some areas, especially in Northern Japan, bears are being seen not just in mountains or forests but in towns and cities. In Morioka, Iwate Prefecture, a bear was seen in the parking lot of a bank. In Gunma, another walked into a supermarket. Between April and August 2025, the Ministry of the Environment recorded more than 3,000 sightings in both Iwate and Akita, and over 1,300 in Aomori. There have already been over a 100 injuries and 12 fatalities this year. In Akita Prefecture, where the number of encounters has risen sharply, the government is dispatching the Self-Defense Forces to assist local authorities.

Japan is a forested country, with about seventy percent of its land covered by trees, and the line separating forests from cities has grown increasingly thin. While the debate about the reasons for the rise in bear sightings and attacks is still ongoing, experts agree that the causes lie both in the environment and in changing social structures. Bears are coming down from the mountains in search of food. Consecutive years of poor acorn and beech harvests have left them without their main food sources. Rural depopulation has also transformed the landscape. The satoyama, or managed woodlands that once formed a buffer between village and mountain, are being abandoned. An aging hunting community means there are fewer people to scare bears away, and many bears have never encountered a hunter in their lifetime at all.

In northern Japan, in Akita’s Ani region, the matagi hunters have long lived in close relationship with the mountains and the wild animals there. Their tradition, which dates back to at least the Heian period, treats hunting as a form of coexistence. A bear is said to be “granted” (sazukaru) by the mountain gods, and after each hunt, the matagi hold a ritual known as kebokai to return the bear’s spirit to the mountains. Every part of the animal is used and shared equally among the group. Today, the matagi are rapidly disappearing as many are now elderly, and few young people are willing or able to take up a way of life that depends on harsh winters. Hunting itself has also become more restricted.

Japan has two species of bear: the brown bear (higuma), found only in Hokkaido, and the Asiatic black bear (tsukinowaguma), found in Honshu and Shikoku. The Kyushu population is thought to be extinct. The brown bear is larger and more aggressive, while the black bear is smaller but increasingly visible in central and northern Japan. While bears are omnivorous, most are primarily herbivorous, with some figures stating that only about ten percent eat ants or other small insects. The popular image of bears feasting on salmon rarely applies here, since salmon are not easily found in most rivers. Most bears spend their lives eating plants, nuts, and fruits, never tasting meat or fish at all. But when food runs low, some develop a taste for meat, and because bears have a high learning ability, it is difficult for them to lose that taste. One view holds that attacks are increasing because the deer population has grown and now consumes much of what bears once ate. Bears may encounter deer as roadkill or abandoned carcasses in the forests and develop a taste for deer meat. When unharvested persimmons, compost, or unsecured garbage offer reliable meals, bears also become used to human presence. And if a bear ever develops a taste for human flesh, there is almost no option other than to kill it.

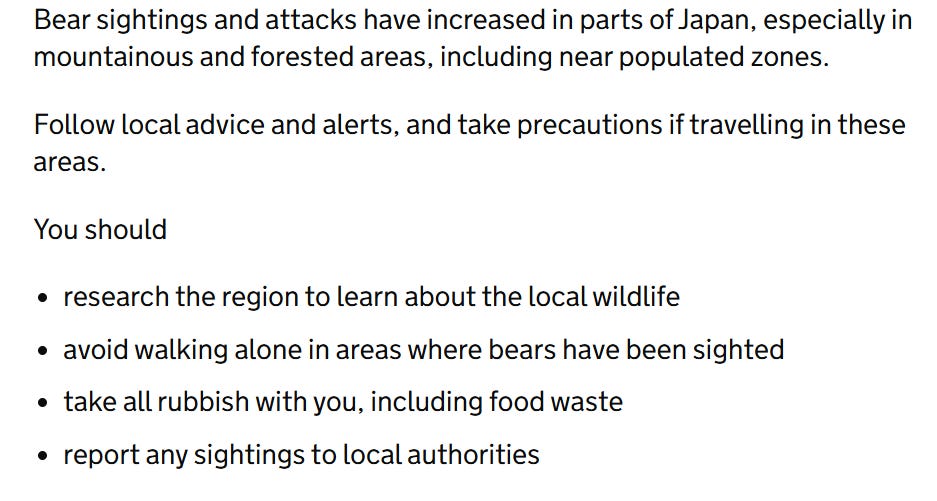

The Ministry of the Environment’s Bear Encounter Response Manual sets out a list of measures to take, the essence of which is to prevent contact wherever possible. The manual also calls to maintain distance between human living areas and bear habitats. Bells have become a familiar sound on Japan’s mountain trails, though they may not work in areas where bears are already used to people. The manual advises pruning fruit trees near forests, securing garbage bins, installing electric fencing, and ensuring coordination among police, local officials, and wildlife officers. For hikers, it suggests carrying a bell or radio but being aware that those aren’t always reliable, checking local warning websites before entering the mountains, and bringing bear-repellent spray.

In September 2025, Japan passed a law allowing local governments to authorize emergency hunting when bears or wild boars appear in residential areas. Licensed hunters can shoot them if public safety is guaranteed. The policy is meant as a last resort, but not everyone supports it and the debate has a long history.

Japan’s most infamous bear attack took place in 1915 in Sankebetsu, Hokkaido, when a brown bear attacked several homes and killed seven people. The incident later inspired Akira Yoshimura’s 1977 novel Kumo Arashi (The Bear Storm), a restrained retelling that treats the animal not as a monster but as a creature caught between hunger and human expansion. In 1970, another tragedy struck when a brown bear killed three members of the Fukuoka University mountaineering club in the Hidaka Mountains. These stories still appear in news coverage whenever new attacks occur. In more recent popular culture, the manga and anime Golden Kamuy, set in early twentieth-century Hokkaido, portrays the brown bear as both feared and revered, reflecting its place in Ainu spirituality and survival.

In recent times, one incident captured popular imagination like no other. In 2019, a large brown bear was spotted in Hokkaido. Over the next four years, the bear injured or killed 60 cows. A footprint measuring 18 centimeters led many to believe it was enormous, much larger than average. Sometimes cows were found with parts of their bodies torn, as if the bear took pleasure in the chase. For local farmers already struggling with losses, it was a nightmare. They could claim insurance only if their cows were found dead, and they had already invested heavily in fodder. A group of hunters began tracking the bear, which came to be known as OSO18, its name carrying an eerie undertone. The media turned it into a sensation, calling it “the ninja bear” for its ability to evade capture. NHK eventually produced a documentary and a book, exploring not just this one brown bear but Japan’s uneasy relationship with wild animals.

While OSO18’s rampage was real, many of the stories around it proved to be myths. The footprint had been mismeasured, and the bear was smaller than imagined. It was likely scavenging rather than hunting for sport. It may have developed a taste for meat after feeding on deer carcasses, a result of the growing Ezo deer population in Hokkaido’s forests. The book highlights the ecological imbalance created by human decisions. In the 1960s, bears were heavily hunted, especially in spring just after hibernation, until they nearly vanished. To protect them, spring hunting was later banned. Meanwhile, Ezo deer multiplied, altering the forest’s food chain and in turn the bears’ diets. Eventually, OSO18 was killed without fanfare and ended up as bear meat served in an eatery in Tokyo. As the NHK book suggests, the human love of a good story may have been what truly created the monster.

Outside Japan, the issue of human–bear conflict is familiar. In North America, national parks use zoning, bear-proof bins, and rubber bullets to deter grizzlies without killing them. In Europe, electric fencing and compensation schemes help farmers coexist with brown bears. Japan’s new policies are moving in a similar direction, aiming for deterrence and distance rather than eradication but in some cases, when bears pose a serious threat, there is no choice but to cull them.

Culling remains controversial. In July, the Hokkaido Prefectural Government faced renewed criticism for killing a bear that attacked and killed a deliveryman in Fukushima, Hokkaido. Many complaints came from people living in cities, far from rural areas, who may not fully grasp the realities of life alongside wild animals. The discussion is not as simple as “us versus them” or giving high handed advice from a high rise building in Tokyo and Osaka while ignoring the realities of bears right outside the doorstep of some communities. Equally there is no denying the impact human activities have on the ecology. As one Toyo Keizai article makes clear, finding a practical form of coexistence with bears is essential. The question is whether we will be able to maintain enough distance and awareness for both species to survive.

Selected references

https://www.env.go.jp/nature/choju/effort/effort12/syutubotu.pdf

https://www.env.go.jp/nature/choju/docs/docs5-4a/pdfs/manual_full.pdf?

https://www.city.sapporo.jp/kurashi/animal/choju/kuma/kadai_taisaku/index.html

https://www.mbs.jp/news/feature/specialist/article/2025/10/108622.shtml

https://www.wwf.or.jp/activities/basicinfo/2407.html

https://kumadas.net/

https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/914905

https://www.city.akita.lg.jp/

If you are prepared, watch this harrowing encounter one hiker had with a bear…

Living in bear country I found your essay quite interesting. There are a number of things one can do to reduce chances of nasty encounters with bears. It's usually a mistake to turn and run from an attacking animal, 99.99% of the time they can run much faster than you. Noise, bear bells as you noted talking etc. a very good idea. Bears have rather poor eyesight but excellent hearing.

A friend of mine, camping, sleeping in the woods awoke with his head in a bear's mouth. He shouted and startled the bear enough that she dropped his head and ran up the hill. The only damage he obtained from the encounter is a scar from one of her teeth in the middle of his forehead.

A lot of ways to reduce the danger but on the other hand, if say the bear has a toothache, or is in a really bad mood for any reason, oh well...

Thank you for that. Having experienced being followed by an unseen large heavy footed animal shadowing me in the trees while taking garbage to our village collection point in the early morning - it’s terrifying